The latest scientific attempt to improve wild deer antler genetics failed to find a practical method that works in the wild, but it helped shed more light on why the genetic “cull buck” remains elusive: Because antler heritability is weak at best. The antlers an adult buck carries on his head, whether they are above or below average for his age, are an unreliable predictor of the antlers his fawns will one day grow.

The Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute (CKWRI) at Texas A&M-Kingsville launched the South Texas Buck Capture Project in the late 1990s, almost 30 years ago. Researchers have captured and measured thousands of wild bucks across numerous ranches in the years since, with many of the bucks being recaptured across multiple years, leading to work on antler growth, the spike question, nutrition, habitat and genetics.

Waves of studies and reports from the project have gradually debunked old myths about deer genetics and culling. Those myths are still not dead. However, they are greatly weakened from many years ago when most hunters readily accepted the false idea that a trigger pull can change wild deer genetics.

The new work is the third major scientific study that tested culling to alter deer genetics and improve future antlers. I’ve reported on two of them already, and this article represents the third. Is it finally strike three for the genetic “cull buck”? Before I tell you about the new study, it’s important for you to be familiar with the first two.

The King Ranch Study

The earliest large CKWRI study I ever wrote about took place at the 850,000-acre King Ranch. Dr. Mickey Hellickson, then still earning his Ph.D., set an extremely liberal target for culls that included any 1½-year-old buck with less than six antler points and any buck 2½ years or older with less than nine antler points. He applied it on a 9,496-acre treatment area on the King Ranch. Meanwhile, researchers culled no bucks on a nearby “control” area of 9,429 acres.

Very few hunters could re-create the optimal conditions for culling, especially the property size and the time and manpower that went into finding and removing cull bucks. Yet, after eight years of very intensive culling, bucks in the control area were just as big, comparing age class to age class, as bucks in the culling area. Natural genetic flow – including factors like yearling-buck dispersal, low reproductive success of any given individual buck, and the genetic contribution of does – overwhelmed the extravagant efforts of researchers to shape antler quality, even on a 9,500-acre study area.

Net-gunning from helicopters is how deer are captured and measured for various Texas studies. It’s also how they are culled, as captured deer that meet culling criteria are sacrificed using scientific research permits. If this intensive, mechanized culling cannot produce genetic change, then recreational hunters most certainly cannot.

The Comanche Ranch Study

Donnie Draeger, a wildlife biologist at the Comanche Ranch, led this study along with co-researchers from the ranch, CKWRI and Mississippi State University. From 2006 to 2015, the scientists used helicopters to capture bucks on three separate treatment areas – a 3,500-acre “intensive” culling site, an 18,000-acre “moderate” culling site, and a 5,000-acre control with no culling. They captured 3,332 unique bucks and culled 1,296 of them.

After seven years of culling, no evidence emerged of successful genetic improvement. I won’t repeat the details of the findings because you can read my original reporting on this study here. But keep this in mind as you read on: During the study, Donnie noted 10- to 15-inch jumps in average antler size across all three sites in years with good rainfall, emphasizing the effectiveness of habitat quality and nutrition in a study that showed culling was ineffective.

The Comanche study collected DNA from all the bucks. Masa Ohnishi and Dr. Randy DeYoung of CKWRI were able to use DNA to identify 963 buck fathers and connect them to offspring. This revealed one of several reasons for the lack of genetic improvement: antler size was not strongly correlated to the antler quality of a buck’s offspring. Some bucks with below-average antlers produced fawns with above-average antlers, and vice versa.

The Faith Ranch Study

The first two studies used culling of existing bucks within the natural breeding ecology of wild whitetails. The third study dispensed with culling and used more artificial techniques to control who breeds who in an attempt to influence future antler quality. The methods used are legal practices in Texas that private landowners can conduct using Deer Management Program permits (DMP). According to Texas Parks & Wildlife, DMP “…authorizes owners of high-fenced properties to temporarily detain white-tailed deer in breeding pens located on the property for the purpose of natural breeding.”

In 2007, the Faith Ranch set up two, 1,100-acre, high-fence enclosures known as the West Yana Pasture and the East Yana Pasture. West Yana included two 5-acre DMP breeding pens within the larger enclosure. West Yana was emptied of deer, while local deer enclosed in East Yana were allowed to stay. Then, helicopters captured deer on a neighboring area, and they were stocked into West Yana’s 5-acre DMP pens.

In one West Yana DMP pen, they placed 15 does and a 176-inch (gross) buck. In the other, 15 does and a 223-inch non-typical buck. These two bucks were local champions – and the envy of whitetail bucks everywhere. They each did their duty with their 15 does in their 5-acre DMP enclosure, and all resulting fawns were captured, tagged, weighed, sexed and sampled for DNA. Then bucks, does and fawns were all released into the surrounding West Yana Pasture. The next year, two more large bucks were captured from outside and placed in the DMPs with a group of does caught within West Yana. This process repeated annually.

Improved nutrition in East Yana alone accomplished more for antler growth than intensive breeding control in West Yana.

Each year, fawns born in the DMPs were tagged and evaluated. Meanwhile, deer in West Yana were captured and evaluated, including fawns born outside the DMP pens. Bucks initially tagged as fawns were caught repeatedly over years and measured. Population density in West Yana was regulated through doe harvest, and the deer were supplementally fed.

If intensive culling of below-average bucks across thousands of acres for years – twice! – didn’t produce measurable genetic change, surely high fences and breeding pens would. Right?

Fast forward to the arrival of Cole Anderson, who is currently working on his master’s degree at CKWRI. Starting in fall 2021, Cole began analyzing 15 years of DNA data from West Yana to build a family tree of fathers and sons, including antler measurements by age class.

East Yana vs. West Yana

Remember East Yana? That’s the matching pasture of equal size next door to West Yana where deer were enclosed, supplementally fed, and managed through doe harvest, but without DMP breeding manipulation. They were just random local deer breeding whoever and however they wanted in their enclosure. Certainly, after 15 years of breeding control in West Yana using only select large bucks, the average 5½-year-old buck in West Yana would produce significantly more antler inches than the bucks in East Yana, right? How much more would you guess?

“About seven inches,” said Cole. “Seven inches of gain after 15 years.”

Buck fawns born inside the 5-acre DMP pens were 10 to 12 inches larger at maturity (5½ to 7½) than East Yana bucks. However, fawns born in West Yana outside the DMPs were only 1 to 5 inches larger at maturity. Combined, the average is about 7 inches larger than East Yana bucks.

Cole found the average 5½-year-old buck in West Yana grossed 152 inches. The average in East Yana was 145 inches. While breeding control did in fact work to increase antler size in West Yana, you can’t ignore the enormous expenditure of time and resources required to add just seven inches to the average mature buck’s gross score.

Cole Anderson analyzed 15 years of DNA data from a Faith Ranch study to build a family tree of bucks and their fawns, including antler measurements by age class throughout life.

Also, we can’t forget the high fence in this study, which should have made genetic improvement easier by containing genetic flow. Cole’s professor Dr. Randy DeYoung was the guest on the July 14 episode of the Deer University podcast, in which Randy said, twice, that he didn’t believe deer genetics could be managed at all outside a high fence. It appears it’s not easy inside one, either.

There’s more to this story, though: The 145-inch average in East Yana is significantly larger than the average 5½-year-old buck in unfed pastures on the ranch, which like most of South Texas is somewhere in the mid 120s. Improved nutrition in East Yana alone accomplished more for antler growth than intensive breeding control in West Yana.

This is the good news for deer hunters like me who can’t afford a helicopter or acquire a permit to net-gun live deer from the air: We can achieve significant improvements in antler quality simply through providing more nutrition for every deer.

Antler Heritability is Weak

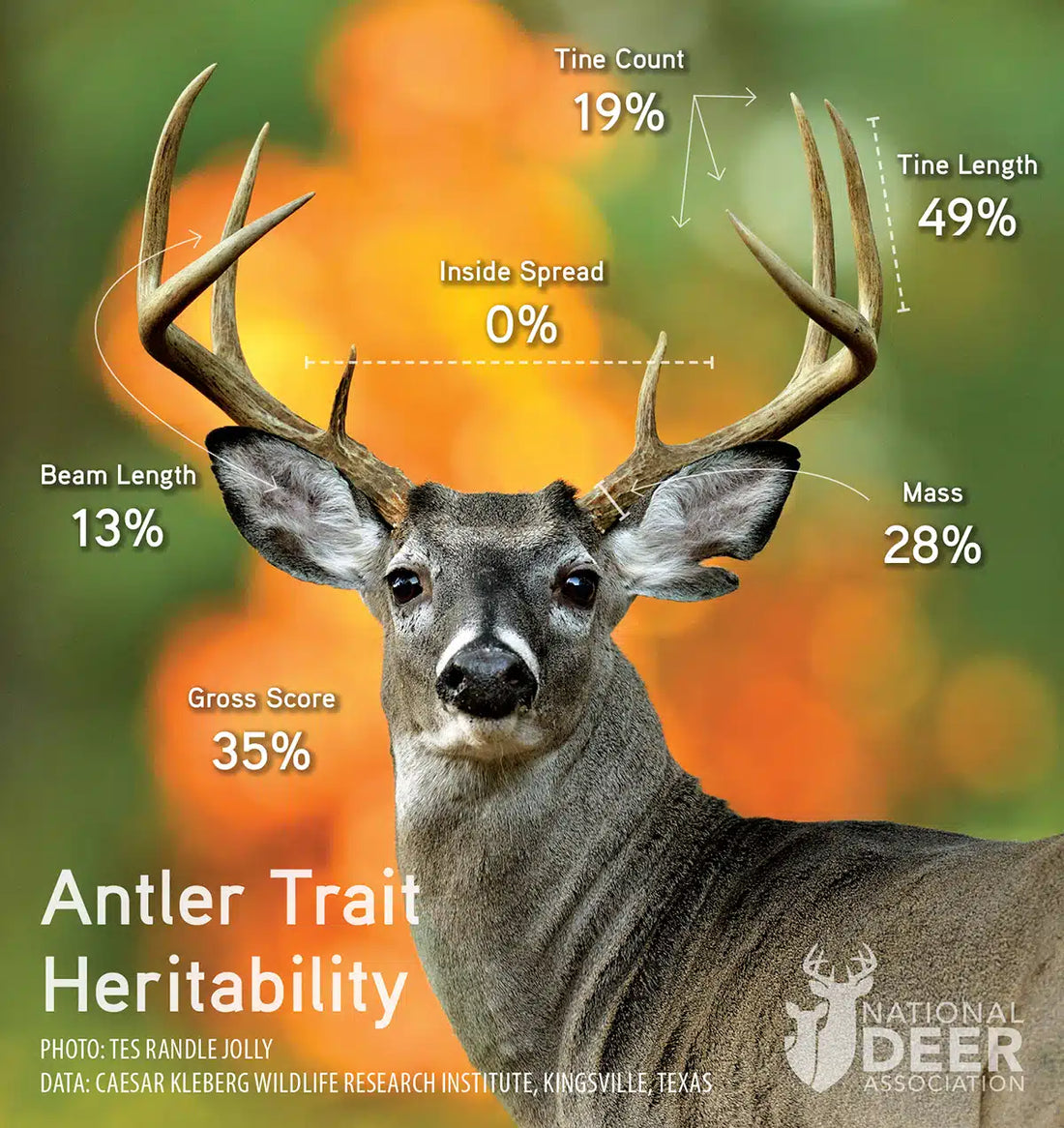

Why didn’t those champion bucks produce a pasture full of champion offspring? Cole found the answer in his DNA analysis as he studied a family tree containing 521 unique bucks and 2,638 measurements of their antler dimensions: Only 35% of a buck’s gross score can be explained by inherited genetic traits. The other 65% is environment, which means nutrition, early life conditions, the doe’s nutrition level during pregnancy, and other factors.

Cole also calculated heritability for specific antler characteristics that make up gross score. You can see these figures in the infographic at the top of this web page.

- Tine length: 49% heritability

- Antler mass: 28% heritability

- Total antler points: 19% heritability

- Beam length: 13% heritability

- Inside spread: Zero. No significant relationship between a buck’s inside spread and the inside spread of his father!

Cole’s finding is simply a more detailed look at the obstacles encountered in the Comanche Ranch study: A buck’s antlers are weak predictors of what his offspring will grow on their heads. Small genetic improvements would require titanic culling efforts – when other leverage points, especially nutrition, work faster and more effectively.

“Let deer grow older, and give them food before you worry about genetics,” said Cole. “Even then, letting them get older and providing good nutrition is going to do way more for you.”

You might think you could select for tine length because – at 49% heritability – it’s the most heritable trait Cole found. “Yes, the chances of success are greater,” said Cole, “but remember it would take a long time and a lot of intensity, and it may not be a huge effect.”

Another confounding factor in manipulation of antler genetics is, of course, the parents who don’t carry visible indicators of their antler genetics. “Does contribute half the antler genetics,” said Cole.

Three Strikes, You’re Out

for hunters of wild whitetails, the facts have been thoroughly checked: We can’t manage genetics of wild deer and produce measurable change. But we can easily manage nutrition to increase deer health, including antler size by age class.

Food plots, forest stand improvement, old field management, prescribed fire, and other tools are available to rapidly increase available nutrition with minimal investment of time and money. Where deer density is too high,doe harvest can also increase available nutrition for future deer. We can also reduce pressure on yearling bucks to increase numbers of adult bucks in the population.

Will this latest study finally convince the hold-out hunters who still believe in the genetic cull buck? Maybe some of them. We just need to keep sharing the facts, promoting habitat improvement, and teaching herd management. I give it at most 30 more years.

This buck had the highest “breeding value” out of 2,503 bucks in the Comanche Ranch study, meaning he produced large-antlered offspring. But his own antlers were only average. He grossed 123 inches at age 6½. As the Faith Ranch study also found, antler heritability is weak.