Author: Lindsay Thomas Jr.

Source: National Deer Association

No matter what deer habitat improvement project you decide you want to try, sometimes the scope of the work can frighten you if it encompasses an entire hunting property, even a relatively small one. I’ve found a way to tame this monster.

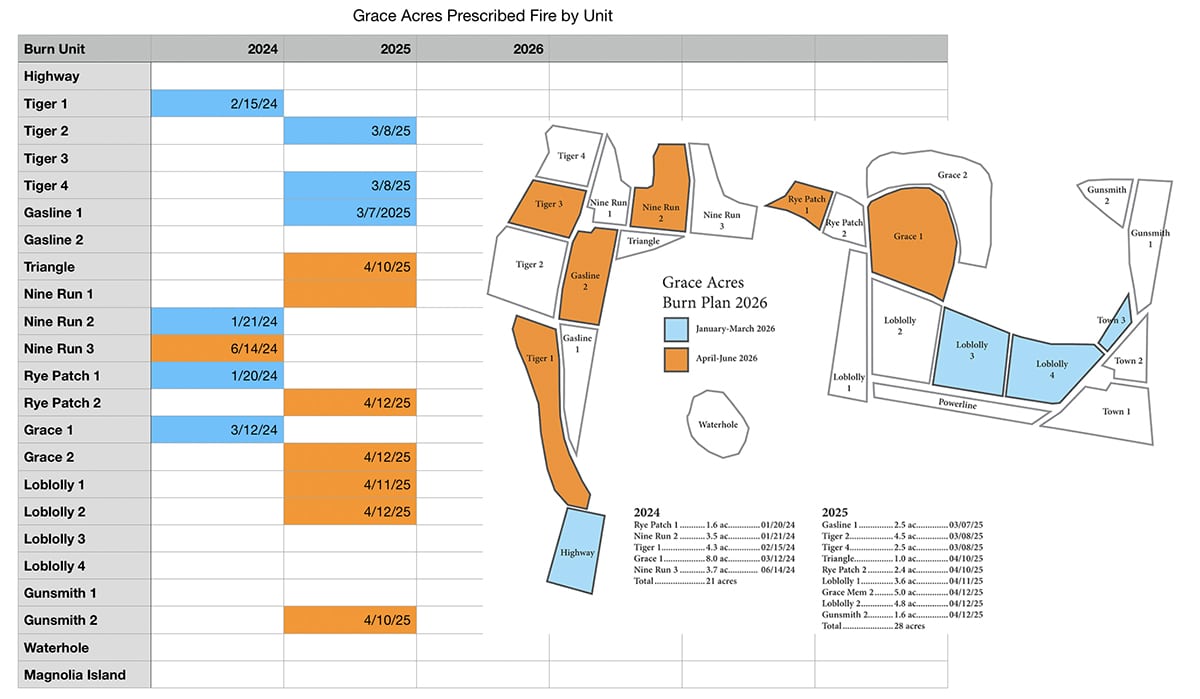

A couple years ago, I got serious about tracking prescribed fire on my family's Georgia hunting land so that I could better manage the timing, frequency, and location of fire for maximum wildlife benefit. I started by dividing our burnable woods into “burn units” on a map. Not only did these units make it much easier to tackle and manage my fire project, I’m now using those units for managing all deer habitat improvement projects. I recommend you carve your hunting land into burn units, too—even if you never plan to burn.

Benefits of Habitat Units

My map of named burn units, combined with a spreadsheet, helps me track the date of all burns and the results. This helps me plan future burns, so I can easily determine which units need to be burned in the coming year and when I want to burn them. But that map of “burn units” is far more useful than just prescribed fire. You might even think of them as “habitat units”—used to help plan all kinds of improvement tasks. Consider these other uses I’ve discovered or plan to take advantage of.

Forest Stand Improvement Units

Just as with invasive-species control, Forest Stand Improvement (FSI) can be overwhelming if you tackle an entire hunting property. Tackle one burn unit at a time. There's natural synergy—FSI opens the canopy, letting sunlight reach the ground, which sets the stage for prescribed fire. Treat shady units with FSI first, then follow quickly with fire.

War Strategy for Invasive Plants

Many avoid managing invasive plants because the task seems too huge. Burn units help break the job into manageable pieces. Don’t try clearing the whole property this year—start with one unit. As you move across units, you'll see native plants reclaim the space.

Fire helps, too. While some invasives resist burning, a burn often forces new growth that’s easier to spray. This burn-and-spray method is helping us control Japanese climbing fern.

Firebreaks as Food Plots

Where burn units meet roads or streams, firebreaks naturally form. Plant these with food plots—disk them, add fertilizer and lime as needed, and seed with perennial clovers, which tolerate shade well. If leaves or pine straw accumulate, walk the break with a blower to keep it clear before burning.

Firebreaks as Shooting Lanes

Even unplanted firebreaks make good shooting lanes for stands. Deer often travel firebreaks as easy paths through heavy cover—making them excellent stand locations.

Firebreaks as Hunting Access Routes

Firebreaks are also helpful for walking and equipment access. They open paths to stands and make hauling deer easier.

Deer Observations and Pressure

Log deer sightings and hunting hours by unit. See which units produce the most bucks per hour and which are most pressured. Use that data to adjust strategies next season.

Shed-Hunting Map

Post-fire is a prime time for shed hunting. Burned ground makes visibility great. Use your burn units map to grid-search without losing track of where you’ve covered.

How Big Should Burn Units Be?

There’s no perfect unit size, but smaller is typically better. A patchwork of 1–5 acre units creates transitional edges, nifty forage-to-cover balance, and easier management. At Grace Acres, we use mostly 5-acre units within a 90-acre burnable area.

Large properties with more support might use 20–30 acre units, but know you lose wildlife benefits when the mosaic disappears. Break up labor and smoke too. Units can always be merged or split as needed.

Dr. Mike Chamberlain (UGA) studies wild turkeys and says: “Smaller is better.” Their use declines on burned stands larger than a few dozen acres compared to smaller patches (@wildturkeydoc).

How to Draw the Boundaries

Use natural features—streams, roads, food plots—as unit edges. In pine stands, thin rows double as breaks. For larger tracts, consult your forestry agency; they often help install plowed firebreaks affordably. Do it before fire season.

In rough or remote terrain, use hand tools—rakes, hoes, chainsaws, leafblowers—to build breaks; just know you’ll need to maintain them manually.

Firebreaks age fast; vegetation grows back quickly. Annual mowing, spraying, or disking keeps them ready for the next burn or use.

Identifying New Ground

My original burn map focused on easy areas. Now I’m expanding into neglected swamps and thickets. By converting those with small paths or breaks, I can incorporate them into management.

That’s the power of burn-unit mapping—you spot neglected corners worth improving. I’ve conquered the deer-habitat monster; now I’m geared up for the bigger fight!

By: Lindsay Thomas Jr.